What Do You Want From a Bible Translation?

I think, for most of us, the answer is obvious: we want an understandable translation that is faithful to the original textual witnesses.

A Bible translation is not helpful or useful if it can’t be read and understood. Nor is a Bible translation helpful or useful if it veers away from what the original authors of Scripture actually wrote. We want something that can be understood when we read it, and something that doesn’t make us wonder where it came from.

Who Will Save Us?

The movie, Sully, is about the real life event of when Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger safely landed a commercial aircraft on the Hudson River after losing both engines from a bird strike shortly after takeoff. Throughout the movie the NTSB (the National Transportation Safety Board) had been investigating the water landing to determine if Sully had actually made a mistake by going for the Hudson when he could have—and should have—headed for a nearby airport.

What Must I Do to Be Saved?

Podcasts are the best.

I especially like listening to The Rewatchables, which is a podcast where a group of 2-4 people discuss their favorite “rewatchable” movies.

During the last episode I listened to they were talking about Ghost. (A movie I haven’t seen before… I know, I know, I should make it a point to watch it.) Since the movie is about someone’s loved one being killed and then returning as a ghost it didn’t take long for the conversation to come to a discussion about the afterlife.

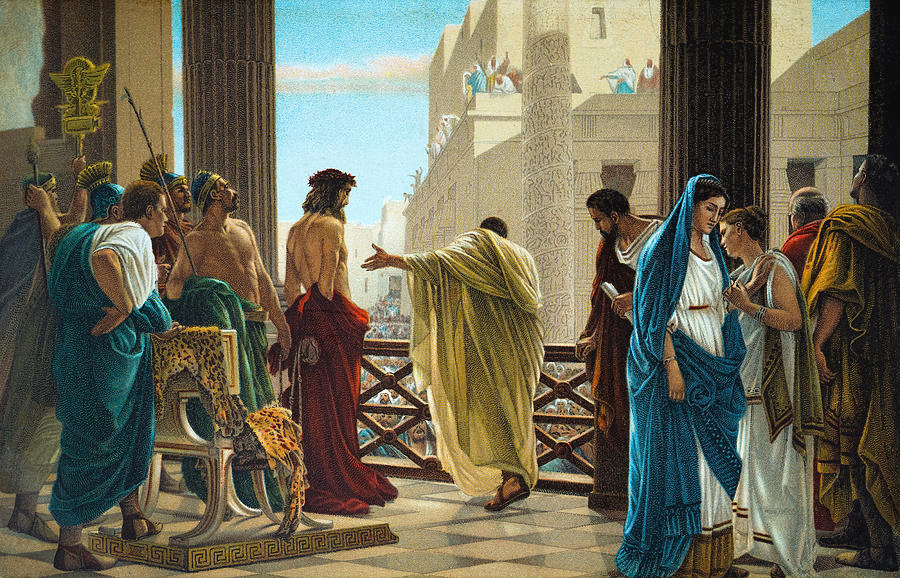

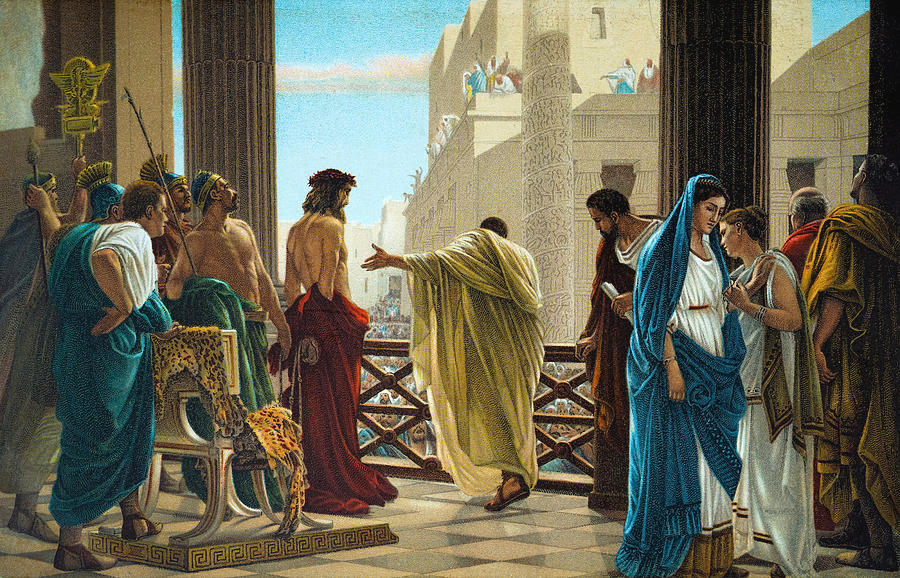

Passion Week: Friday - The Beginning of the End

If the beginning of the end wasn’t when Jesus rode into Jerusalem as a king, it most assuredly was when Judas brought a crowd to arrest him. From that point forward Jesus would no longer walk freely throughout the land with his disciples. From here on out he’d be bound, either by chains or by nails to a cross.

Passion Week: Wednesday - The Scheme

What do you do with a person who says and does things that invite others to believe that he is not only the king, but God in the form of a human being? If you don’t like his message of kingship and divinity, you come up with a plan to end all this nonsense by getting rid of him.

Translate That!

It just needs a little elbow grease.

If you are a native English speaker, you know exactly what that means.

Certainty With Uncertainty in the Biblical Text: Luke 23:34

When we think of Jesus, forgiveness is usually one of the first topics to come to mind.

A Moment on the Scriptures: The Order of the Hebrew Scriptures

In what order were the Hebrew Scriptures originally put together?

Can You Really Trust Luke to Tell a True Story?

It doesn’t take long to see how people’s memories (short-term or long-term) aren’t always the most reliable.

Hebrew, Greek, and Luke 3:4b-6

One of the great things about giving your time to biblical studies and regular bible reading is—like with most things—you start to see things you never saw before.